Photo courtesy of Nottingham Live and is of coal picking, Bestwood Colliery c1912 Strike for a District Minimum Wage

Throughout the 19th century coal miners and their families, including those in Nottinghamshire, faced hunger in the bad times and poverty and hardship when the economy boomed. In addition, major mining disasters claimed thousands of lives. Miners and their families also had to face intimidation and bitter opposition to their attempts to establish a trade union.

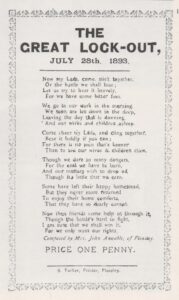

Poem: The Great Lock Out 1893. Photo courtesy of A R Griffin, The Nottinghamshire Coalfield, 1881 – 1981.

With the aid of their emerging trade union (the Nottinghamshire Miners Association), and their courageous leaders, from 1844 onwards coal miners battled to reduce their hours of work, have their output fairly weighed and valued, (with the introduction of checkweighmen), be paid a living wage, improve mine safety and protect themselves from intimidation and unemployment.

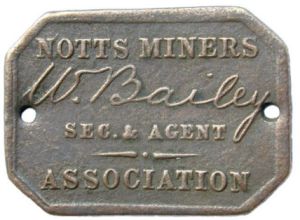

W Bailey, 2nd Agent of the Nottinghamshire Miners Association Photo courtesy pf www.mining-memorabilia.co.uk

There were many strikes and Lockouts throughout the 19th century, when miners struggled to feed their families and defend themselves from the ‘iniquitous ‘sliding scale’ agreements, which saw their poverty wages further reduced when coal prices slumped. The Union’s leaders were frequently victimised and effectively blacklisted as they could not find employment in any pits in their area.

The 1844 Union was crushed when its leaders were sacked and only those who signed a document agreeing not to join a Union, were allowed back to work.

In 1863 The Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire Miners’ Association was established. This Union had to be organised in a ‘clandestine’ fashion until 1866 because of the bitter opposition of the coal owners. The Nottingham Review reported in September 1866,

“that the owners of the Staveley Pits were ‘determined to crush the Unions”.

Strike breakers were introduced from various parts of the country including Cornwall. At a meeting at the Three Tuns, Hill Top, near Eastwood in January the following year it was reported some of the owners offered to pay the men 3d per ton extra if they agreed to leave the Union. The men pledged themselves to stand firm behind the Union.

By November 1867, however, the Union was unable financially to support further action. Those who had stood out to the end were unable to find work; their late employers would not have them and a system was introduced to make sure they would not find work in the pits elsewhere.

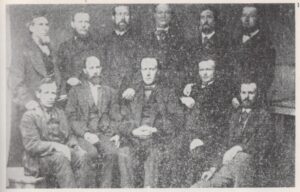

In May 1874 the 11 Committee members of the Derbyshire & Nottinghamshire Miners Association, who had taken a leading part in the dispute, were victimised and refused employment. Many of these men were local preachers. In the photograph their names are as follows: Back row: S Shooter, G Brown, S Cox, G Taylor, T Vickers, J Stratham. Front row: J Seal, W Purdy, T Wheeldon, J Wright and T Purdy. A descendant of the Purdy’s, Dick Purdy was an NUM Branch Official at Ollerton and later Training Officer at Clipstone Colliery.

Leaders of the NMA 1874 who were victimised after the dispute. Back row S Shooter, G Brown, S Cox, G Taylor, T Vickers, J Stratham; Front row: J Seal, W Purdy, T Wheeldon, J Wright and T Purdy.

In 1889 most of the District Unions, including Nottinghamshire, overcame their reluctance to join together and the Miners Federation of Great Britain was born and in 1890 the MFGB joined the Trades Union Congress.

In 1893 the coal owners proposed a 25% decrease in wages. At this time there was already a great deal of suffering in all mining villages, including in Nottinghamshire. When the miners refused to accept the wage reduction they were locked out. Nationally some 300,000 were locked out.

Children of striking miners in South Derbyshire eagerly awaiting food in Swadlincote Town Hall. Bread, cheese and meat was provided by an anonymous donor from Liverpool, known as ‘The Stranger’

In Nottinghamshire, by September 1st, the Union only had £2,000 left in its funds and its outgoings on strike pay were £7,000. It was decided that the Union would issue Promissory Notes to members in lieu of cash. These notes were to be used to purchase goods from local traders and were redeemable at some future date. These notes were signed by William Bailey and Aaron Stewart for the Union and A R Griffin says, in his book, ‘The Miners of Nottinghamshire, Vol 1, 1881 to 1914,

“It says a great deal for the character of the men that their signatures were apparently looked upon by local shopkeepers as being sufficient guarantee.”

A number of local churches paid the proceeds of their collections into union funds, the two Bulwell churches among them. In addition the Bulwell church undertook to provide dinners for some 700 children who attended the national schools. These dinners were provided daily throughout the dispute.

The Lock Out lasted 16 weeks and at the end, the miners sacrifices were rewarded. A R Griffin says

“They had won because, in spite of great suffering, they had remained loyal to their leaders and their principles. For generations, miners had had to work for whatever wage their employers had thought fit to give them. Now at long length they had won a living wage and they had shown their determination to keep it.

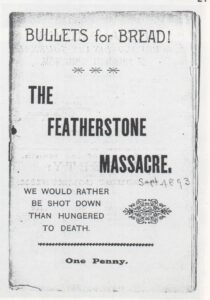

Featherstone Massacre leaflet. Photo courtesy of A Century of Struggle: British Miners in Pictures, 1889 – 1989

The 1893 dispute featured a shocking event when the forces of authority deliberately turned out soldiers from the local barracks and marched them to Featherstone Colliery; there following a reading of the Riot Act the soldiers opened fire on the crowd. Two men were killed and 16 were injured.