Fact Sheet 1

The Explosion 1866 saw England’s worst ever mining disaster at, The Oaks Colliery, Barnsley.

Wednesday 12th December 1866.

Oaks Colliery

About 1.15 pm – The first explosion ripped through the underground workings of the Oaks Colliery. It could be heard 3 miles away! Dust and soot from the pit covered the ground at Cudworth 5 miles away.

It was near the end of the day shift and the pit was full of men and boys. Absenteeism was very low as Christmas was near and Wednesday was making up day for pay.

2.00 pm – Three rescuers went down into the pit. They found 20 badly burned miners and sent them up to the surface. Only 6 of these miners recovered.

Soon about 70 volunteer rescuers were underground. They found that the workings were full of after-damp (Carbon Dioxide CO2) which was caused by the explosion. They struggled to breathe in the confined tunnels underground. Eventually they went into the main part of the mine, the main underground tunnel (known as the ‘Engine Plane’). They discovered it was full of miners collapsed on the floor. Fathers and sons were found embracing each other. Pony drivers with their horses were found together, all had been overcome with deadly after-damp gas.

By late afternoon, early evening volunteer rescuers had to be turned away as there were too many of them.

At 10.00 pm a prominent local mining engineer arrived called, Parkin Jeffcock, together with a man called Tewart, the under viewer, he supervised work underground all night. He wanted to get the air circulating around the mine again.

Thursday 13th December 1866. 8.30 am –

Most of the rescuers evacuated the pit for fear of another explosion. Jeffcock and his men carried on with their work.

9.00 am – The pit exploded again. It sent the cage into the headgear. 28 men including Jeffcock and Tewart were still underground.

7.40 pm – A third explosion saw flames roar up the shafts. The pit was on fire.

Friday 14th December 1866.

4.30 am – The signal bell sounded on the surface indicating that someone was alive underground.

A bottle of water and brandy was lowered into the mine and taken. A makeshift pulley was erected and two brave men named, Mammett and Embleton rode down in a large metal bucket.

A man, Samuel Brown was found alive at the bottom. He had been knocked unconscious by the second explosion and had somehow survived. He was brought to the surface.

Saturday 15th , to Tuesday, 18th December 1866.

There were another 14 explosions until the decision was made to abandon the rescue and fill in the shafts to smother the fire underground.

5th November 1867

It was finally safe to start clearing the shafts. In all it is estimated that 361 men and boys were killed. The exact cause of the explosion is not clear other than methane gas was ignited by an unknown source.

Fact sheet 2

Some Mining Terminology

This is not a definitive list but should help with understanding the disaster where the terms are used.

Engine Plane – an underground tunnel (roadway) along which tubs are conveyed to and from the “workings” to the pit bottom by engine power.

Cage/Trunk – the “lift” that travels up and down the shaft carrying men, coal and materials into, and out of, the mine.

Lamp Cleaner/Lamp Cabin – men who are in charge of safety lamps in the colliery. The cabin is where safety lamps are allowed to be opened underground and cleaned or repaired. Naked flames are not allowed outside the cabin.

Inbye – going into the mine away from the shafts.

Outbye-is going back out of the mine towards the shafts.

Drift – a horizontal passage underground following the bed of coal. This can be at a gradient.

Fire Damp – Methane gas. If mixed with the right quantity of air (8%) it will ignite/explode, if exposed to a naked flame.

After Damp/Black Damp/Choke Damp– are terms for Carbon Dioxide which displaces oxygen after explosions of fire Damp leading to asphyxiation.

Underviewer—A supervisor of the coal mine. He receives orders from the manager and directs underground operations.

Viewer– is an old name for the mine manager.

Level—another name for an underground roadway.

Jinney– a method of using weight of a full tub to raise an empty tub self acting on inclines underground.

Overcast– An important ventilation bridge where one airway passes over another.

Passbye—a siding, or widening of the roadway that allows yubs of coal to pass one another underground.

Roadway—a tunnel underground which men and materials travel to and from the pit workings.

Engineman—a miner who controls an engine for hauling tubs.

Engine Plane– an underground roadway that the tubs are hauled along to and from the workings.

Shaft—a vertical hole in the ground which air, men and materials are taken in, or out of the mine.

Furnace shaft/Upcast Shaft –shaft wit a large fire near to the bottom which enables a current of air to be drawn around and out of the mine.

Head Gear— the pulley frame erected over the shaft.

Pit Mouth or Pit Bank—top of the shaft.

Cribs—cast iron or wooden rings that support the shaft sides.

Sump—the bottom of the shaft below the lowest inset.

Banksman—the man who works in the pit mouth area.

Lundhill— an area near, Wombwell, Barnsley. The site of a colliery which exploded on February 19th 1857. a total of 189 men and boys were killed in the Lundhill colliery disaster.

Fact sheet 3

The Oakes Colliery in Context

The Oaks Colliery had been called various names since its opening, The Great Ardsley Main, Ardsley Main, Ardsley Oaks, Old Oaks, and, The Oaks Colliery. Later Barnsley Main Colliery stood near to the site. Some historical dispute surrounds when the Oaks Colliery was first opened. Sources give the date somewhere between the 1820’s, and 1830’s.

Any understanding of the Oaks Colliery disaster of 1866 needs to be seen in the character and context of Victorian Britain. A possible starting point of the tragic events of 1866 could be the equally tragic events of 1838.

On Wednesday, 4th July, 1838, a fierce thunderstorm led to a series of disastrous events which would leave 26 children dead. The children were employed underground in the Moorend Colliery, near Silkstone, Barnsley. The rain had dampened the steam engine used for winching miners in and out of the pit. In their juvenile haste the children had sought an alternative route out of the pit by means of a day hole, the Husker drift; unbeknown to them the drift had flooded. The children aged from 7 to 17 were drowned when they became trapped in the flooded drift.

The horrific tragedy was the latest in the grim catalogue of early 19th century mining disasters, and accidents. Stunned into responding the young Queen Victoria ordered a public enquiry which led to the 1840 “Royal Commission of Inquiry into Children’s Employment”. One result of the inquiry was the, 1842 Coal Mines Act, which, excluded all women and girls and all boys under the age of 10 from underground coal mine employment.

1845 – At “Ardsley Main” miners went on strike. The men complained that the price they got for “cutting a yard (of Coal) on end had been reduced from 3s 6d to 3 shillings and that corves which had held 6 ½ hundredweights were replaced by ones 1 which held 8 without any increase in wages. They demanded to be paid by weight and the appointment of their own checkweighman (A miners appointed scrutineer to oversee the coal weighing process ensuring fairness and correct payment for coal produced). Their request was refused. It was also “chillingly” stated in a newspaper that the pit was “a dangerous one in which to work” and because of this it would be difficult to find “blacklegs” to take the places of those on strike.

1847 – Friday, 5th March, (First) Oaks Explosion. – 73 miners killed. “The county’s first really serious explosion” On Monday, 8th March 1847, the coroner’s inquest was held in the, White Bear, Hoyle Mill, (Today it’s called “The Hoyle Mill Inn”) the verdict of the jury – Accidental Death. The following extract from the verdict is alarming given that 19 years later, in the same pit, another explosion would spread more and greater misery.

“The jury are also of opinion, that efficient regulations are not enforced in this district to prevent the use of naked lights in those parts of coal mines in which inflammable gas is known to exist; and are further of opinion, that the recurrence of accidents involving so large a loss of human life, demands the immediate attention of Her Majesty’s Government, and would justify Parliament in passing such a Code of Regulations as would give greater security to persons employed in mining operations; and they further request that their verdict and sentiments be forwarded to the secretary of state for the Home Department.” The coroner briefly expressed his approval of the verdict, and signified his willingness to accede to the request of the jury.

1850 – Coal mines Inspection Act – This act was introduced, to a certain extent, in response to the growing public concern at the frequency of accidents in mines. The Act increased the number of mine inspectors to four. Further, it empowered them to make underground inspections, view mine plans, and produce reports into the conditions and safety in mines. The inspectors were placed under the supervision of the Home Office.

1851 – Three miners killed by explosion at the Oaks Colliery.

1855 – Coal Mines Inspection Act. The first effective step to enforce standards and safety in coal mines. It required the observance of a number of rules.

20th June 1856, Oaks Colliery. Nearly 400 men ceased work because, “a fear which has of late come over the miners of accidents being caused by the alleged incompetence of their resident manager”. The colliery owners refused to discharge the manager and the resultant strike lasted 10 weeks. The manager was not dismissed.

17th February 1857, (Five months after the Oaks miners had returned to work) there was an explosion at Lundhill Colliery where 189 miners were killed. It was established that while the air current entering the pit was sufficient, ventilation on the coal face was unsatisfactory and the observance of the general and special rules was not strictly enforced. Management was lax and the method of working the coal was dangerous.

In 1860, Yorkshire’s 387 collieries produced 9,284,400 tons of coal in a year.

1860 Coal Mines Regulation Act. This Act improved safety rules and raised the age limit for boys from 10 to 12. It also provided for the appointment of a checkweighman.

16th January 1862, Hartley Colliery disaster, Northumberland – Miners entombed when the engine beam broke and blocked the only working shaft. 204 killed. Single shaft working had been condemned on countless occasions before 1862 but to no avail. The result of this tragedy was an Act to amend the Law relating to coal mines whereby from, 1st January 1865, there had to be at least two shafts or outlets in every colliery.

1866 the annual output of coal in Great Britain exceeded 100 million tons, for the first time. Annual output achieved, 101,754,294 tons, from, 3,192 mines, by 320,663 miners. Coal mining accident statistics for 1866 showed that there was one death for every 216 men and boys employed and one life lost for every 68,484 tons of coal mined in British Coalfields.

In 1866, a group of women organised a petition that demanded that women should have the same political rights as men. Their petition and demands were defeated in the House of Commons but, The London Society for Women’s Suffrage was formed with similar groups forming all over the country. The Suffragette movement had begun.

10th December 1866, at a council meeting of the Miners Union, then called, The South Yorkshire Miners Association, The Ardsley Oaks branch of the association had 275 members. The following meeting on the 7th January 1867 records show the membership was 16.

12th and 13th December 1866, – The Oaks Colliery Explosion results in the worse loss of life in an English Coal mine. 361 miners would lose their lives.

All the information contained in this blog is courtesy of the “Oakes Disaster 1866” visit their Website www.oaks1866.com, for more information.

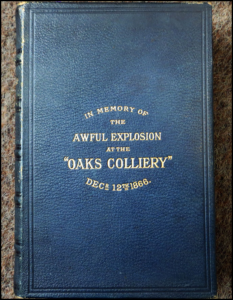

This said to be a the large metal bucket known as a “Kibble” used to rescue

Samuel Brown.