Our blogs this month, feature excerpts from a presentation by one of our Directors, Ann Donlan. Ann charts the relationship between the appalling poverty found in 19th and 20th century coalmining communities and the dangerous nature of a coalminer’s working life and the industrial and political campaigns waged to improve the lives of coal miners and their families. These campaigns led eventually to the public ownership of the mines in 1947 and the creation of the NHS in 1948.

Poverty in coal mining communities in the 19th and 20th centuries

Poverty was endemic and widespread in coal mining communities in the 19th and 20th centuries.

This photograph is of a Soup Kitchen run by church people in Bulwell for miners’ children during the 1893 lockout. Strikes and Lockouts (where the miners were locked out of their workplace until they accepted the employers’ terms, mostly less than they currently earned) were frequent occurrences.

Mining Trade Unions were gradually organising throughout the 19th century. The Nottinghamshire & Derbyshire district of the Miners Association was formed in 1844. The Association led a 5 month strike for better wages, but under pressure from coal owners and the Government it was crushed.

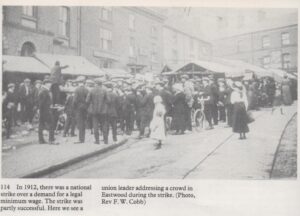

In 1912 there was a national strike over a demand for a legal minimum wage, which was partly successful. This photograph is of a strike leader addressing a crowd in Eastwood, during the strike.

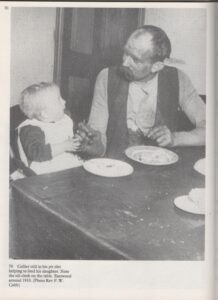

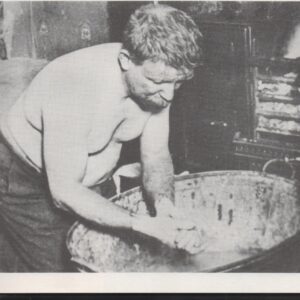

These photographs are scenes from mining life and all photographs are taken from “The Nottinghamshire Coalfield 1881 – 1981” by A R Griffin.

In 1919 Sidney Webb, a socialist, economist and reformer, asked

“Why do twice as many babies die in a miner’s cottage as a middle class home?”

The mortality rates for babies between 4 weeks and 1 year in miners families was 4 times that of professional workers.

One of the Honorary Members of the Nottinghamshire NUM Ex and Retired Miners Association, Ida Hackett, (sadly no longer with us)

– whose father was victimised at the Warsop Maine colliery in the 1921 strike was only able to get a job four years later at Bentley Colliery. As an 11-year-old during the 1926 strike, she remembered that:

“families had to survive on soup made from bones from butchers and vegetables from their allotments. She later recalled: “We didn’t have soup kitchens. There were real food kitchens in village halls and schools.“

The Times, on the 28 March, 1928

Exposed what it called the ‘social disaster’ in South Wales, where there were over 100,000 registered unemployed and where many miners had already been out of work for two or three years. The newspaper stated that the poverty of the unemployed and the low paid, together with the handicap of debts incurred in 1926, meant that boots and clothing and household goods could not be replaced. The Times stated:

“today men and women are starving; not starving outright but gradually wasting away through lack of nourishment.”