For this Mining Blog, we are remembering the Bilsthorpe Mining Disaster that occurred on the 1st March 1927 in which 14 men lost their lives.

We would also like to pay tribute to the people of Bilsthorpe for their very moving Memorials erected in the Memorial Garden and the Churchyard and which speak volumes about the community’s determination to remember all those who lost their lives in the three accidents in the mine. 14 men lost their lives in this accident in 1927; 9 men lost their lives at the mine in 1934 and 3 in 1993. The Davy Lamp in the Memorial Garden records the names of the 76 men and 1 woman who died in accidents at the pit.

In its report published the same day as this accident, on the 1st March 1927, the Nottingham Evening Post described the accident thus:

“FLOOD DISASTER AT A NEW PIT NEAR MANSFIELD”

“14 MINERS DROWNED”

“TERRIBLE DISASTER AT NOTTS COLLIERY”

“RESCUERS BATTLE AGAINST RISING WATER”

“Seventeen pit-sinkers working on the staging in the shaft, were precipitated to the bottom, owing to the water-pipe breaking away, and carrying the staging with it, and it is feared that 14 have been drowned.”

“Pathetic scenes were witnessed at the crowded pit-head and burly miners wept for the loss of relatives or friends.”

14 men had indeed lost their lives.

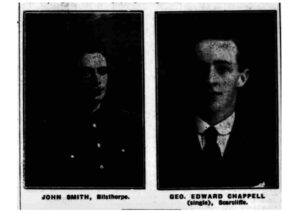

3 men were rescued: John Smith, 26, Edward Chappell; and Fred Williams, 27.

We thank the British Newspaper Archive and the British Library Board for this text and the following images.

Newspaper image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

These are photographs of two of the rescued men, John Smith and Edward Chappell.

Two survivors of the Bilsthorpe Colliery Disaster. John Smith and Edward Chappell. Photograph Nottingham Evening Post, 1st March, 1927. Newspaper image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

Chappell and Williams deserved the highest commendation for their courage and presence of mind during the eight hours it took to get the three out of the pit.

This is the full report for which we thank the www.healeyhero.co.uk website for the text and research – follow this link to the report on that site Bilsthorpe 1927 – Page 1 (healeyhero.co.uk)

And the Northern Mine Research Society Bilsthorpe Colliery Shaft Accident – Bilsthorpe – 1927 – Northern Mine Research Society (nmrs.org.uk)

BILSTHORPE. Bilsthorpe, Nottinghamshire. 1st. March, 1927.

This was a sinking accident and the site of the new shaft was about seven and a half miles due east of Mansfield. Two shafts of 20 feet 2 inches diameter were being sunk within a lining and the work was started in July 1925. The coal had not been reached at the time of the disaster. The arrangements at both shafts were the same and on the 1st. March the No.1 shaft had reached 278 yards, 20 yards deeper than the No.2, and was lined with concrete to 253 yards. Below this lining the side of the shaft were supported by 4 inches of 1-inch iron rings about 4 feet apart with backing sheets of corrugated iron behind held tight by wedges. The lowest ring was about five feet from the bottom of the shaft.

Water had been encountered at 63 feet and below this point, cement was injected into the surrounding strata to keep out as much water as possible. as sinking proceeded the shaft was lined with concrete 16 inches thick at the top gradually increasing to 25 inches at the last length that was completed. A steam pump dealt with water to a depth of 150 feet and then that was replaced by a Sulzer electrically driven centrifugal pump which was designed to deliver 1,000 gallons per minute against ahead of 1,040 feet. This was driven by a three-phase motor developing 500 h.p. The combined motor and pump weighed 14 tons and was suspended in the shaft by as steel rope fixed at one end of the headgear, passed down the shaft and under a pulley on the pump unit and from there back up to the drum of a capstan engine by which the whole was raised or lowered as required. The electrical cable which supplied power to the pump passed through another hole at one side of each pipe clamp and was held there by special clamps.

At the time of the accident the total weight of the pump unit, rising main full of water, clamps, cables and suspension ropes was 40.29 tons. The suspension rope was 7 inches circumference and was made of the beast acid grade steel wire with a breaking strain of 161 tons. The walling scaffold was suspended on two other ropes attached to separate capstan drums which were 79 feet above the shaft bottom at the time of the accident.

At about 7 p.m. on the 28th February a round of sumping shots had been fired and so far as could be judged they had done their work. From then on the work was to fill out the ground broken by the shots and the pump which had been raised the usual 18 to 20 feet out of the way while the shots were fired, was lowered back into its normal position. The amount of water to be dealt with at the time was about 12 to 15,000 gallons per hour. The pump was lowered a few inches at a time as the debris was cleared from the bottom and the last time it was lowered before the accident was at 1.30 a.m. on the 1st March.

There were 21 men working in the shaft and at about 2 a.m. they began to go to the surface in relays for their snap. When the third batch of men including the pump attendant left the shaft bottom everything seemed to be in good order but before they reached the top the pump “jacked” (began to draw air) and on the signal from the bottom the current was cut off at the surface. On arriving at the top the pumpman decided to go back to restart the pump and went down in the hoppit with men who had finished their snap. The hoppit had been lowered to the “steady” a point about 18 feet from the bottom when it stopped until a further signal was given before it was lowered right to the bottom. At this point the men at the surface heard a crash and the greater part of the rising main, from the surface to about 169 yards down the shaft, collapsed into the bottom of the sinking pit. At the same time the electric cable drum was jerked from its foundation and pulled over towards the shaft, the cable itself being damaged about 150 to 160 yards down the shaft but it was not broken. The pump suspension rope was not damaged. The engineman felt a jerk on the winding rope and tried to raise the hoppit but found it was held down by the debris.

The hoppit was trapped at the bottom of the shaft, the winding rope was cut at the surface, recapped and a new hoppit fitted. This was lowered down the shaft until it came to the lower part of the rising main which was found to be standing but was leaning across the shaft and prevented the hoppit making any progress.

Shouts could be heard from the shaft bottom and another rope was lowered from the hoppit with a safety belt on the end. Three men were still alive at the pit bottom, Frederick Williams, George Edward Chappell and John Smith. Williams was on the pump ladder when the accident happened and was struck by falling material but managed to hold on to the ladder and eventually took shelter behind the pump. The two others were in the hoppit. After debris had stopped falling, Williams got to the hoppit which was at the side of the pump and he found that Chappell and Smith were alone but injured. Chappell was able, with assistance, to get up the ladder to the walling scaffold but Smith could not move and to prevent him falling into the shaft bottom which was filling with water, Williams got him to the pump landing and tied him with a muffler and a handkerchief to the pump.

During the hours that passed before they could be rescued, Williams went up and down the ladder shouting for help from the top and calming Smith. When the safety belt came down Chappell put it round Smith and guided him through the scaffold to safety. Smith was terrified and reluctant to make the journey. Shortly afterwards two more ropes were lowered and Williams and Chappell were both drawn to the top and safety. Chappell and Williams deserved the highest commendation for their courage and presence of mind during the eight hours it took to get the three out of the pit.

Williams had examined the men in the hoppit and found that they were dead and a careful inspection of the shaft was made by Mr. Todd, the Agent, Mr. Linley, the Manager, Mr. J.R. Felton and Mr. W.E.T. Hartley, both H.M. Inspectors of Mines. Mr. A. Gee, the contractor and Mr. J.T. Brown, master sinker. The lower part of the rising main was dismantled and this work was complete at 3 a.m. on 2nd March when the walling scaffold was reached and the body of John Robinson recovered. Access to the other bodies was delayed by the rising water in the bottom of the shaft and the necessity to replace the rings and backing sheets which had been knocked out.

The water in the shaft was lowered to within 33 feet of the bottom by means of a large water barrel but owing to obstructions in the shaft, this was the lowest to which the water could be reduced. There was a feeder coming into the shaft and 26 tons of cement was injected and the feeder was reduced to 3,000 gallons per hour. After this steady progress was made and the remaining thirteen bodies recovered, the last of the 15th March.

The inquiry into the disaster was held in the 22nd. and 23rd, June 1927 in the Guildhall, Nottingham, by Mr. Henry Walker, C.B.E., H.M. Chief Inspector of Mines and presented to Colonel the Right Honourable E.R. Lane Fox, M.P. Secretary for Mine on 25th. July 1927. All interested parties were represented.

The possible causes of the accident were:

- A broken clamp on the rising main.

- A defective joint on the rising main.

- A fall from the side of the shaft striking the rising main or the pump.

- The grounding of the suction pipe on the bottom of the shaft.

There was no evidence of a defective joint or a fall from the side of the shaft. The key witness was Frederick Williams and he gave an account of the accident as follows:

Q: Now Mr. Williams just tell us what did happen at that point?

A: Something came from above, struck me on the back of the head and the shoulders, and took my feet off the ladder, from under me, but I happened to have a good hold with my hands, and I scrambled out as best I could.

Q: It is rather important for us to know what did happen. Did you hear a noise at all?

A: The noise came with the crash. It all came at the same moment.

Q: Did the pump swing at all at that time?

A: As the crash came she swung but she was perfectly still before.

Q: Can you give us any idea of how long this crashing was going on?

A: Well the main crash did not last long, but the stuff was falling up to the time I came from there. That was from the sides around. But the main crash itself did not last very many minutes.

Q: Was that main crash, as you call it, above or below you?

A: It came from above me.

Q: Did you, before that, hear anything below?

A: Everything was as quiet as it could be, because they were all quiet owing to waiting for me to shout for the chargeman to start the pump.

Q: The man in the bottom were not working, were they?

A: Every man was stood keeping quiet, until the signal.

Q: So that the shaft at the time was particularly quiet?

A: Yes.

Q: If there had been any movement it the bottom would you have heard it, do you think?

A: Oh yes, at that time because the pump was not working. It was as quiet as the grave, as you might say.

It may have been that the blow which stunned Williams was the result of a clamp breaking high up on the rising main but the evidence of Professor S.M. Dixon of the Civil Engineering, City and Guilds Engineering College, London who examined the clamps thought they were excellent and in good order and F Lea, Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Dead of the Faculty of Engineering at Sheffield University agreed with Professor Dixon.

A sinker, Norman Mason, who lost his brother in the disaster said that the following the firing of the shots the pump was lowered too far and bumped the shaft bottom and Horace Hunt, a pump fitter, had complained about one of the joints leaking. Professor Dixon said that of joints were weakened; the long term effect would be that the pipe would eventually collapse.

Henry Walker came to the following conclusions:

I regret that I am not able to state the cause of this accident but I am clearly of the opinion that the occurrence of a similar accident can be prevented.

In the system followed at Bilsthorpe and elsewhere, the pipes forming the rising main column are supported merely by standing one upon another, the clamps serving only to keep the column